Visual Language of the Failed Painter

"I am a failed painter, but the painter never dies in me." ~Orhan Pamuk

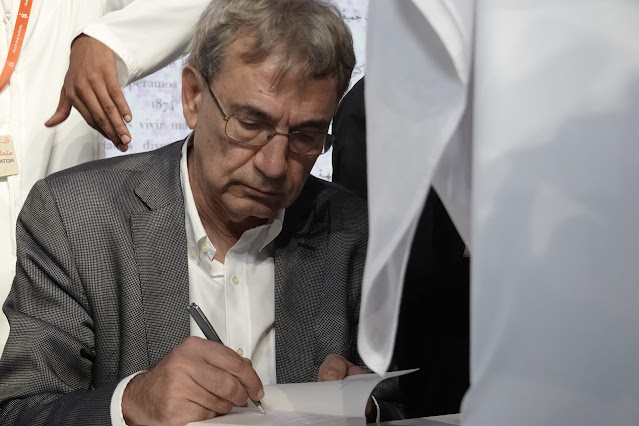

At the end of October 2019 in Sharjah, UAE, I attended a talk show that presented Orhan Pamuk on the stage of the Sharjah International Book Fair. He spoke about the reasons for writing and freedom of expression in Turkey.

At the end of the event, a long line of attendees waited their turn to get autographs on the books by Pamuk that they had brought with them. Orhan Pamuk looks relaxed, he is willing to serve conversations and photo requests in a friendly manner.

That night I developed the impression that Orhan Pamuk is a successful writer who's not distancing himself from his readers. A world-class writer who is uncomplicated and not arrogant. I have started collecting and reading Pamuk's works since then.

Recently, when I was looking for information about Orhan Pamuk's latest novel, I was surprised to find that Pamuk's last two books were not novels, but photo books entitled Balkon (2019) and Orange (2020). Both are published by Steidl, the world's best photo book publisher based in Germany.

This is unique, I thought. It is rare for a novelist, whose reputation has won the international highest recognition of the Nobel Prize for Literature (which he won in 2006), is also a photographer with two books at Steidl. I became interested in finding out more about the background that took the most popular Turkish writer in this new direction.

It turned out that this change in direction was actually nothing new for Pamuk. Presenting works in visual language for him was like returning to his original passion. Indeed, when Orhan Pamuk was young, he dreamed of becoming a painter.

Orhan Pamuk was born in 1952 in Istanbul, "the city of ruins and end-of-empire melancholy". He never lived in another city in his life. From the ages of 8 to 22, he was passionate about painting. His family supported his studies in art and architecture. However, mysteriously his passion for painting suddenly disappeared and Pamuk turned to write novels.

What made him do that? In various interviews with him, Orhan Pamuk said reading many novels had made him move from painting to writing. At the age of 23, he found his passion in reading the great works of world writers.

"I read so many novels that I was crazy. Just like the character in my novel The Silent House. Reading novels has changed my life. Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Thomas Mann, Borges, Calvino ... Finding these writers, was like the experience of seeing the sea for the first time in your life. You're stuck there. Want to be like that. "

So, actually it's not a mystery. Reading novels has diverted his aspirations from visual language to verbal language. His first novel Cevdet Bey was published seven years later, in 1982, and to date, he has written more than 20 novels. Many of them have won international awards, have been translated into more than 60 languages, and have sold more than 13 million copies.

However, Pamuk never really left his painter's soul in him. Painting art and the stories of painters are themes that often appear in his books.

After about ten years of establishing a career as a writer, he began to want to write about the joys of painting, how it feels when a painter makes brushstrokes on canvas. From here was born My Name is Red (1988), which tells the mystery of the murder of a 16th-century Turkish miniaturist painter.

Pamuk likes to write about the relationship between the joy of seeing, and the joy of expressing in words what the eye sees. Presumably, he did this to compensate for his failure to become a painter.

As a writer, Pamuk admits that he has never experienced writer's block because he always prepares well before writing. Detailed outlines make it easy to move to another section if you're stuck. Still, writing doesn't always flow smoothly even for someone like Pamuk.

By the end of 2011, depression and writing impasse had driven him to a new preoccupation: taking pictures. From December 2011 to April 2012, he obsessively took 8,500 photos from the balcony of his apartment to get a panoramic view of the city of Istanbul, the Bosphorus entrance, the old city, the Asian and European side of the city, the surrounding hills, and the mountains and islands in the distance.

Pamuk said the desire to take photos obsessively was related to the mood he was in. About 500 of these photos were later published by Steidl in a book entitled Balkon.

"I recognized my own sorrow in the landscape. And they distracted me from my melancholy state," he said at the book launch event in New York.

Orange is the second photo book, born from his observation that street lamps with the warm orange lights, which has been a hallmark of the streets and alleys of Istanbul since he was a child, are slowly being replaced by lamps with cold, pale white lights.

He wanted to capture this before the night view of Istanbul completely changed and people forgot about it. The photographs in this book were all taken from dusk to late-night time over a span of decades, as a routine activity of walking that Pamuk did after a day of writing, including for the purposes of researching his book between 2008 and 2014.

In the introduction to the book, he recounts how the photos he intended to record the "last orange glow" of Istanbul's night, at the same time recording the rise of nationalism in several circles of society through posters and flags posted on their homes.

From the type of clothing that people wear on the streets, the photos record a resurgence of religious sentiment if compared to twenty years ago when police would still arrest people who disobey secular dress codes. And it also recorded an increase in the number of Syrian immigrants from the looking of people who passed along his night-journeys of taking pictures.

These two photo books appear to be consistent with Pamuk's other works. He keeps telling about his beloved hometown in the same vein as his novels.

It's even in-line for the reason that the Nobel Prize committee mentioned in awarding him: "In his search for the melancholy soul of his hometown, he has found new symbols for conflicting and intertwined cultures."

"The soul of a painter never dies in me," said Pamuk. And the novelist combines it perfectly in his works. He has stopped painting, now it is the visual language of photography that becomes a remedy for his soul when he is faced with deadlocks.

From a photographic point of view, the tone of the photographs in both books tends to be monotonous. There is not much variation in perspective, no attempt to get closer to the people being photographed. But the importance is in the documentation. For now, let's enjoy these two books while waiting for Pamuk's next work, which is said will more and more combine these two things: words and photos.

Look like balcony are source of inspiration for artist and photographers. I really ignore details of his life but I happy to see how is strong connection between photo and literature... Thanks to share.

BalasHapusYes, both are creative expression. Thanks

Hapus